Inefficiencies in supply chains are exacerbated by disruptions to demand, such as the recent panic buying at supermarkets worldwide following COVID-19-related shutdown announcements. UNSW’s Professor Sami Kara explains how the ‘bullwhip effect’ typically resulting from sudden changes in demand impacts siloed agrifood supply chains – and how taking a systems approach to streamlining supply chains can dampen this effect, curbing food loss and improving responsiveness to customer demand.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, 52 per cent of all fruits and vegetables in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are lost in the supply chain before ever reaching consumers (FAO, 2011). Part of the reason for this high level of food loss is inefficiencies in agrifood supply chains.

Introduce a source of major disruption into an already-inefficient food supply chain and these losses grow. Take the COVID-19 pandemic, for example.

“What we are experiencing in food supply chains domestically and globally as a result of COVID-19 is not because of the lack of capacity but because of disruption or perturbation along the food supply chain and the different KPIs of supply chain partners,” explains Professor Kara, UNSW Scientica Education Fellow and Director of Vertically Integrated Projects in the University of New South Wales’ Faculty of Engineering.

“Shortages of goods in supermarkets we saw as the pandemic hit were the result of the disruption of the customer demand signal, due to COVID-19, and the lack of robustness of our existing supply chains,” Prof. Kara says.

“Shortening these supply chains by producing closer to consumer is one way to address this problem at the source. This is what urban vertical-farming ventures like [CRC participant] Sprout Stack are doing.

“However, doing this at the whole agrifood industry level requires other strategies, which are part of the core business of the Future Food Systems CRC.”

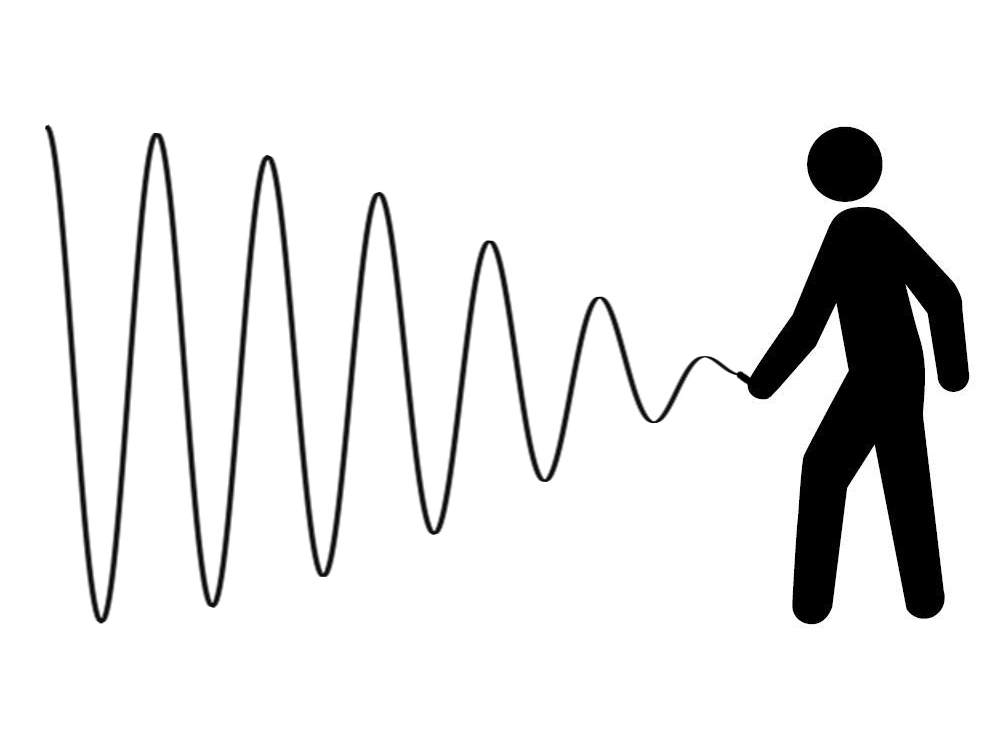

The bullwhip effect: typically, demand signals are amplified as they travel upstream in supply chains. Credit: Gusts Must be Ambulatory, via Wikimedia CC

What is the ‘bullwhip effect’?

The ripple of repercussions in a supply chain that results from a major disruption such as a pandemic is known as the ‘bullwhip effect’.

“In supply chains, product flows downstream from producers to consumers. Dollars and information, on the other hand, get passed on upstream from consumers to producers, influencing what is produced,” Prof. Kara explains. “As information travels through the supply chain, variations, caused by various reasons in sales downstream, translate into increasingly distorted orders upstream.

“The further [you get] from the originating demand signal, the greater the distortion of the wave pattern. In a similar manner, forecast accuracy decreases as one moves upstream along the supply chain.

Typically, the distortion of initial demand signals as they travel along a supply chain results in more goods being produced than are needed ‘upstream’.

“Producers end up producing goods in higher batches to compensate [for] this inaccuracy,” says Prof. Kara.

“This has serious implications for all participants in the supply chain, not just the end consumer – such as higher inventory-keeping costs, and lack of transparency about the quantities of finished goods that are located at any one time within the supply chain.”

The bullwhip effect in agrifood supply chains

Within the food and agriculture sectors, the bullwhip effect can prove especially costly. And increased customer requests for fresh products only compound the issue.

“In the horticulture sector, the problem is exacerbated by the perishable nature of the product in the supply chain,” Prof. Kara explains. “At the height of the pandemic in Australia, fruits and vegetables – produce that is highly perishable and is usually delivered and consumed fresh – saw significant losses across all links in the supply chain.”

In the food sector, the bullwhip effect is intensified by “poorly aligned incentives across the supply chain, and the lack of system design of these supply chains”.

The trouble is that rather than seeing their supply chains as integrated wholes, working for the benefit of all parties along the chain, participants are viewing just their bit of the supply chain, in a siloed, self-serving way.

“As a result, each supply-chain partner tries to optimise their own business – which, in turn, leads to an unsatisfied customer at the end,” Prof. Kara says.

Why does the bullwhip effect happen?

“The reasons behind [the bullwhip effect] are twofold: firstly, traditional inventory management practices; and secondly, the response of supply-chain partners to market changes due to their unique KPIs,” says Prof. Kara.

Take the widespread shortages of items such as toilet paper and non-perishable foods. “There was no actual shortage in this situation,” he contends. “The problem was caused by a supply chain blockage up the line.”

A recent New York Times article explained the issue thus: “One of the myriad reasons we’re having trouble finding toilet paper and pasta online is that Target and Amazon limit the quantity of products they stow in warehouses,’ the article states. ‘That saves them money when shopping behavio[u]rs are predictable, but it leaves less flexibility when demand spikes unexpectedly.’

Prof. Kara sees similar problems in food supply chains linking farmers and processors to retailers, noting that ‘black box’ operators in these chains can “seriously sacrifice the supply-chain’s integrity and transparency”.

What are supply-chain ‘black boxes’?

Some time ago, leading procurement and supply chain academic Professor Richard Lamming argued that, in the future, the vast majority of the work in supply chains would be automated, explaining this via an amusing story about a black box, a man, and a dog.

‘The black box would carry out all the routine procurement work – establishing internal requirements and specifications from internal stakeholders, talking to suppliers’ black boxes to agree pricing, delivery schedules, managing the purchase to pay process and so on,’ explained writer Peter Smith in a 2012 article on the topic. The man’s role would be to turn on the black box each morning; the dog’s, to attack the man if he tried to turn off the black box.

According to Lamming, the man (or woman) in the story could still play a meaningful role, as a deal maker and key stakeholder relationship manager. But supply-chain relationships would be, for the most part, ‘black box to black box’.

Microgreens growing in Sprout Stack’s vertical farming facility in Sydney; the company is looking to Prof. Kara and his team to help it streamline and scale up its operations. Credit: Sprout Stack

A more integrated, streamlined supply chain:

Kara aims to change the ‘siloed’ approach to agrifood supply chains, in part via a collaborative research project with CRC industry participants.

The proposed research project is “taking a systems view of the problem”, says Prof. Kara, and has multiple aims:

- to develop “a tactical/operational control concept that enables firms to lead the ‘pull signal’ of customers’ orders through the entire distribution chain to the front end of production planning” – in this way becoming better able to control the replenishment of customer‐facing distribution centres and warehouses, or even crop production, according to real customer demand;

- to identify how this ‘pull‐controlled’ supply chain system – with a higher number of smaller, more dynamic warehouses; different means of transportation; different shipping volume; et cetera – affects the supply-chain network layout;

- to develop new network design solutions that work to shorten and streamline supply chains by producing closer to the customer, establishing food hubs via industrial symbiosis, et cetera; and

- to produce real‐time data monitoring technologies and policies that enable firms to trace goods easily within its supply chain, leading to greater transparency and increasing the robustness of that supply chain.

A customer-driven supply chain

It is hoped that by taking a systemic approach, Kara and his research team can significantly improve the network design so that the company’s supply chain is more responsive to changing customer demand.

Which means getting fresh plant and animal products from farm to fork faster and more cost-effectively, with less waste and fewer emissions along the way.

“The long-term objective is to do this type of system design work for all the producers in the CRC, and eventually, to develop a commercial tool that can help other agrifood businesses do the same,” says Prof. Kara. “Our goal – to streamline supply chains – is in line with the core aims of the Future Food Systems CRC, and is very much aligned with the objectives of the fresh food industry.”

Developing such a tool will take about three years, he says, but it is timely work – and the resulting tool should prove commercially valuable to Australian food producers, especially those looking to export.