Could the presence of a specific strain of bacteria in a person’s gut make infection more likely on exposure to SARS-CoV-2?

A recent paper published by UNSW-based scientist Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh and his co-authors calls for further research to test their hypothesis that high levels of specific bacteria in the human gut may be linked with poorer COVID-19 outcomes.

Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, a professor in the School of Chemical Engineering at University of New South Wales, and colleagues published the perspective in the May 2020 issue of ACS Nano.

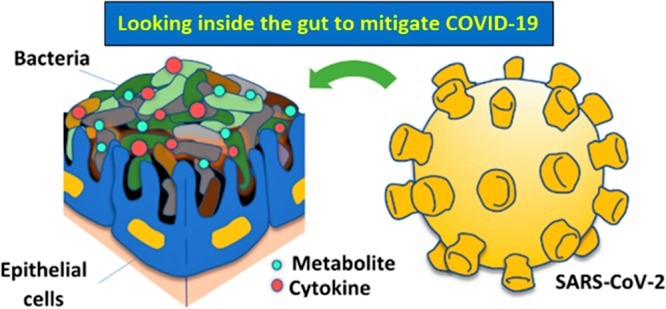

The paper looked at the likely impact of dietary patterns and the commensal microbiome – an area that to date had been largely ignored. In their perspective/hypothesis paper, the authors presented a rationale for urgent investigation of the potential impact of the gut microbiome on SARS-CoV-2, including looking at potential therapeutic options for SARS-2 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on modifying patients’ diets and thus, their microbiomes.

Gut bacteria in COVID-19-vulnerable populations

“The first clue was the link between those more vulnerable to COVID-19, who are the elderly [and] people with underlying health problems such as cardiovascular disorder, type 2 diabetes and hypertension,” Professor Kalantar-Zadeh says.

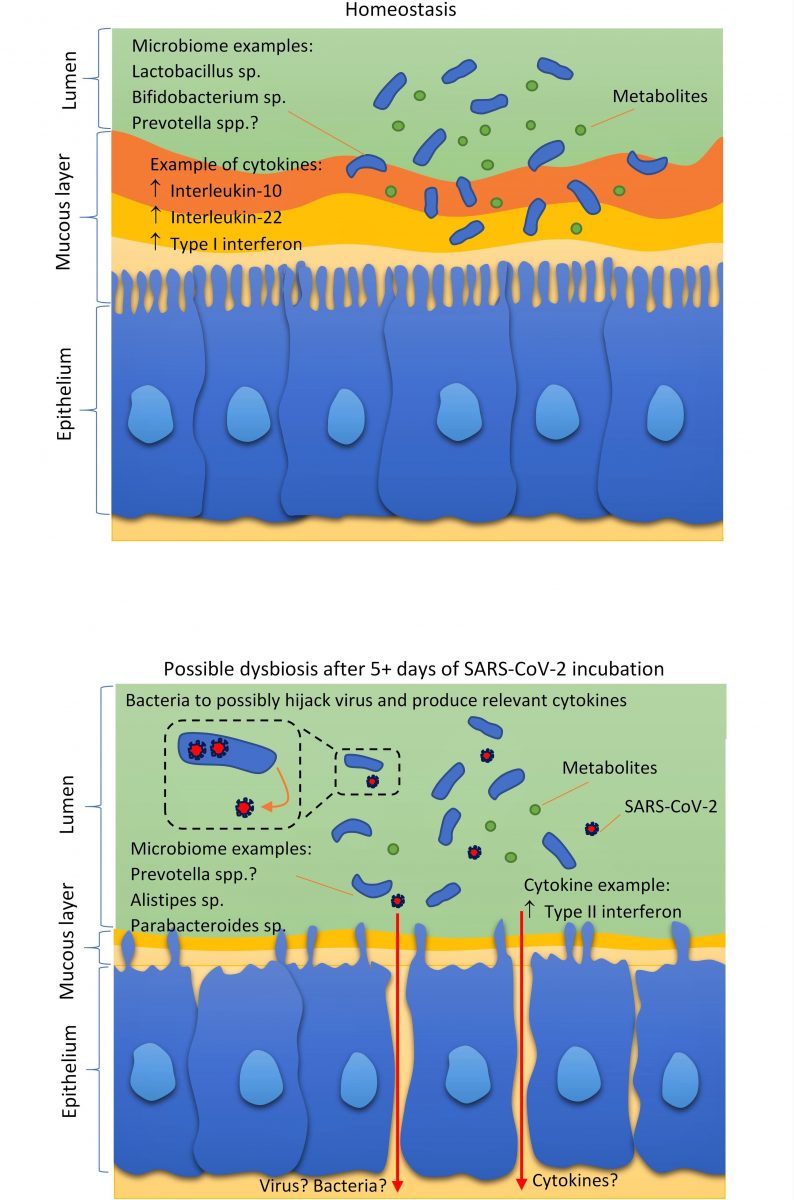

Ageing, the paper notes, is associated with significant shifts in microbiome diversity and pro-inflammatory states – with strong interindividual variability ‘that may explain, in part, the different impacts of viral infections in elderly individuals’.

“The second link was several initial papers showing the possible high abundance of specific bacterial strains in clinical samples of COVID-19 patients,” notes Prof. Kalantar-Zadeh.

Such specific microbiome shifts are also seen in the elderly, and in asthmatic and diabetic patients. For instance, numbers of the H2-producing bacteria are ‘highly enriched’ in obese individuals prone to type 2 diabetes, while an abundance of Bifidobacteria – which can produce butyrate – in type 2 diabetes patients has been shown to improve glucose tolerance.

“The third set of clues are recent papers that show the possibility that viruses can modulate or be modulated by the gut microbiota,” Prof. Kalantar-Zadeh adds.

“The last clue was that gut disorders are seen in many COVID-19 patients; and the fact that COVID-19 is a two-stage process disease – five days’ initial incubation versus less than a single stage two-day incubation period for normal influenza – gave me more confidence that the virus is first possibly hijacks the gut and its commensal bacteria (in the first five days) and then impacts different organs in the human body,” the professor explains.

“Putting these clues together and exploring recent papers, we came up with the hypothesis that one or several of the gut bacteria can initially promote the virus one way or another. The core microbiome can modulate or be modulated by the virus.”

Medium-scale trials support microbiome link

Several medium-scale human trials have so far tested this hypothesis to show that the morbidity of COVID-19 patients is associated with their long-term dietary patterns and that the core microbiomes of COVID-19 patients are modulated.

These trials so far support the UNSW scientists’ hypothesis and lend weight to the strategy of improving our dietary habits. They also support further investigating the link between the gut microbiome and SARS-CoV-2 virus impact.

“Large, adequately powered international studies that recruit COVID-19 patients and controls to collect clinical data, detailed dietary assessments, host genetics, immune phenotyping and multi-site, multiomic microbiome markers should be conducted to learn more,” Prof. Kalantar-Zadeh says.

Nutritional and dietary strategies: building a better microbiome

Until more is known about which microbiota strains are most useful or harmful in this respect, Professor Kalantar-Zadeh advocates adopting high-quality nutritional and dietary strategies as a potential means of suppressing viral infection and mitigating the harmful effects of SARS CoVid-2, particularly in the elderly and those with underlying health problems.

‘One approach … could include strengthening the intestinal barrier against pathogens, increasing intestinal motility, and reducing an underlying pro-inflammatory state by adopting a more varied diet with a moderate increase in high-fibre and plant-based foods,’ the authors state in their report.

“High-fibre, diverse, moderate-calorie diets, high in fresh fruit and vegetables, low in fat and very low in sugar, and including some freshly fermented foods, could likely reduce the severity of the disorder,” Prof. Kalantar-Zadeh explains.

Following a healthy balanced diet, states the report, is ‘a logical approach to mitigate the severity of this viral infection as a plausible preventive action’. Such an advice is in agreement with the Australian Government Department of Health under its ‘Healthy eating during coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions’ guidelines.

Further information

For further information, contact Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh at the School of Chemical Engineering, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW; email: k.kalantar-zadeh@unsw.edu.au.